By Manash Firaq Bhattacharjee

The results of the five-state assembly polls have spelt hope for secular Indians, as the Hindutva camp examines its political reverses. A rejuvenated Congress in the Hindi heartland has halted the rising saffron tide in India’s political landscape.

In Rajasthan, where the state BJP government last year reduced Gandhi and Nehru’s significance in India’s freedom struggle and elevated the status of V.D. Savarkar in school textbooks, where farmers committed suicide facing high loans and low productivity, the party lost 89 seats.

Also, in Rajasthan – where a daily-wage worker, Mohammad Afrazul, was hacked and burnt alive, and Abdul Ghaffar Qureshi and Rakbar Khan were lynched by vigilantes – there India’s first ‘cow welfare minister’ lost the elections by 10,000 votes.

In Chhattisgarh, which Amit Shah claimed was “almost free of Naxalism” under the Raman Singh government, the BJP lost 34 seats.

In Madhya Pradesh, the BJP lost 56 seats. In an election rally in Bhopal, the UP chief minister, Adityanath, had remarked, “You keep your Ali, for us Bajrang Bali will be enough.” Such proclamations could not prevent the BJP’s Humpty Dumpty of communal politics from having a great fall.

Apart from Congress’s victories, the BahujanSamaj Party and the Samajwadi Party reiterated their commitment to secular politics by extending their support to the Congress. This has rekindled the possibility of a joint opposition against the BJP in the Lok Sabha elections in 2019.

There are other indications for hope.

In the last four years, we have seen the media act as propaganda machines against political opponents. People were turned “enemies” of the state overnight. The state machinery was complicit, and police often played spectators to violence carried out by right-wing mobs. Although the Sanghparivar has implanted its ideology into pockets of civil society, students, journalists and activists openly defied the idea of a Hindu Rashtra.

It is difficult for the Hindutva project – borrowed from a European nation with a homogenous religious identity – to whip up a similar political campaign against a religious minority, given India’s rooted heterogeneity. That is why the racial roots of anti-Semitism can’t be easily translated into the politics of Islamophobia. India is a country of converts.

There is a hybrid culture of belief in India, where Hindus visit dargahs and Muslims celebrate Diwali, where Kabir sings of one god and castigates caste, while Muslim poets elevate the idolatry of the beloved to the status of divine love. Engineered events of violence can create temporary wedges between Hindu and Muslim neighbours, but old, cultural habits of life take over. The still waters of democracy run deep in India.

The pyramidal structure of power exemplified by the Modi government has been both openly and covertly criticised by older members of the BJP. This partly comes from a long political investment in the idea of democracy, despite the right-wing mindset, and partly from a general concern about dictatorial power in India’s political culture. The BJP has been the most vocal critic of the dynastic politics of the Congress, but today it finds itself in a similar structure of power where Modi and Amit Shah wield the position of the party “high command”.

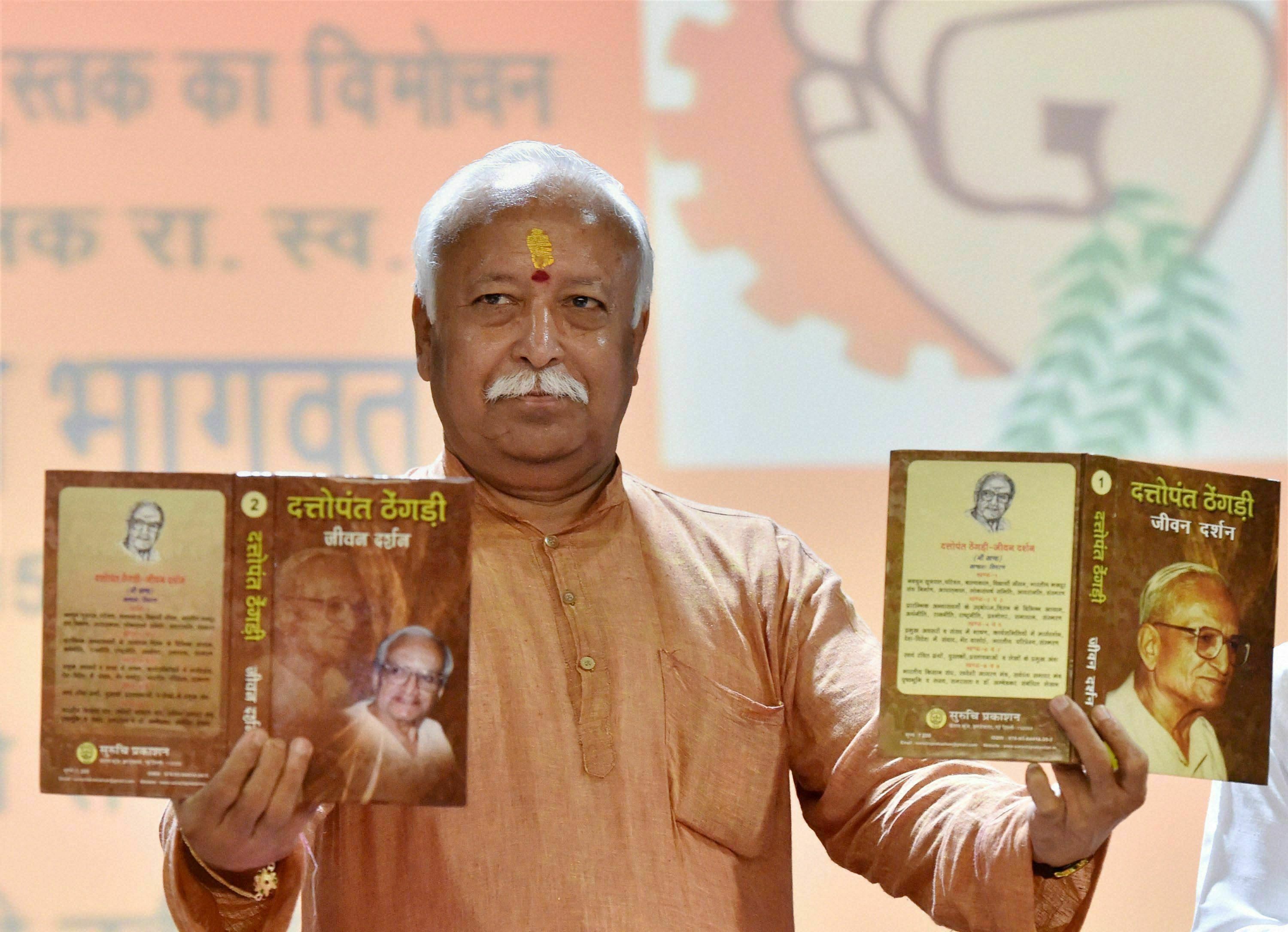

At the World Hindu Conference in Chicago in September this year, held to commemorate the 125th anniversary of Swami Vivekananda’s historic speech at the parliament of world religions in 1893, RSS chief Mohan Bhagwat metaphorically spoke of Hindus being tolerant enough to “recognise even the rights of pests to live”, but warned of the risk of the unprotected, lone lion being devoured by “wild dogs”.

‘Pests’ and ‘wild dogs’ are metaphors that leave little to the imagination. Earlier this year, Amit Shah used the synonym “termites” for describing Bangladeshi migrants in Assam.

Contrast Bhagwat’s language with what Vivekananda said in his address in 1893: “I am proud to belong to a nation which has sheltered the persecuted and the refugees of all religions and all nations of the earth” [emphasis added]. As a “way of life”, what we understand as tolerance, or offering refuge to the persecuted, Vivekananda and Bhagwat’s ideas are quite radically apart.

In his essay, ‘Attenborough’s Gandhi’, Salman Rushdie observes that the film does not mention either the name or the organisation of the man who killed Gandhi. In the film, writes Rushdie, “the killer is not differentiated from the crowd; he simply steps out of the crowd with a gun. This could mean one of the three things: that he represents the crowd – that the people turned against Gandhi… that Godse was ‘one lone nut’… or that Gandhi was Christ in a loincloth, and the assassination is the crucifixion”.

This dangerous game of representation is useful to keep in mind. The deliberate uncertainty accorded by members of the BJP to the lone wolfs and lynch mobs belonging to the Hindu Right is meant to achieve two things: One, to blur the identity of those people. Two, to suggest they are ordinary folks from civil society.

But like Godse, these people are not part of the crowd. They belong to vigilante formations influenced by Hindutva. In Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan and Chhattisgarh, the shadowy organisations that carry out violence have lost, however narrowly, to the real, ordinary, democratic crowd of voters.

Bhagwat, in the Hindu Conference at Chicago, pointed out what appeared to him a tragic irony: “Coming together of Hindus itself is a difficult task”. The opposite of unity is not necessarily disunity, but social and cultural diversity. It is the radical heterogeneity of Indian society that frustrates the Hindu Right despite its prolonged attempts at widespread communal mobilisation.

Even the aspirations of the radical Left, which thrive on a homogenised idea of class war, meet this unique resistance. Apart from diversity, another crucial form of resistance to communal politics that represents a Brahminicalmindset and order inevitably comes from the political movements of the underprivileged castes.In a speech delivered on April 4, 1938, Ambedkar made the remark that for the first time in India’s history, there was “a feeling that we are all one… due to the fact that we have a common government.” Governmentality and its juridical document, the constitution, forged the idea of one people among Indians. This basis of India’s social unity, for Ambedkar, was in sharp contrast to the lack of unity that prevents Hindus from constituting a society in the modern (Western) sense.

As Ambedkar saw, not only did caste deny Hinduism “a unified life and a consciousness of its own being”, but caste also “prevented society from mobilizing resources for common action in the hour of danger.”

Ambedkar’s critical point regarding caste hindering the “militarisation” of Hindu society faced with a “catastrophy like war”, acquires the status of a political deterrent when underprivileged castes resist the militarisation of Hindu society based on Brahminical values. Along with the disgruntled and angry farmers, who did not vote for the BJP in MP, Chhattisgarh and Rajasthan, and the beleaguered Muslims, the small but electorally crucial gains of the BahujanSamaj Party in these three states are a case in point.

Finally, the avalanche of statues and change of names of roads and railway stations in the country, show a hurry to institutionalise and memorialise exclusively the contribution of Hindus in Indian history and culture.

There is a supremacist agenda behind this project. It is legitimised by sentiments that were aired, among many others, by V.S. Naipaul, when he said about the Babri Masjid demolition: “The sense of history that the Hindus are now developing is a new thing. Some Indians speak about a synthetic culture: this is what a defeated people always speak about.”

Naipaul was fanning a narrative of humiliation. But you cannot insult a people to remind them of their – real or exaggerated – humiliation. The Hindu Right is currently insulting Hindus’ intelligence and ethics by telling them they need to be united for – not against – hatred.

Discover more from The Kashmir Monitor

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.